Apex II Launch 2

We decided that a dawn launch would be an interesting thing to do, since it has not been done that often by people in the HAB community, and would provide the potential for some truly fantastic photos. The date of 09/04/11 was decided upon as one launch was already planned from the CUSF launch site at Churchill College on that day, and it was a weekend where many of the Apex team were free. Sunrise on the ground was determined to be at 0618BST, and we decided to aim for sunrise at 20km. As such, we deduced that sunrise at 20km would be at 0551BST, and a 5m/s ascent rate meant a launch time of 0444BST.

Payload

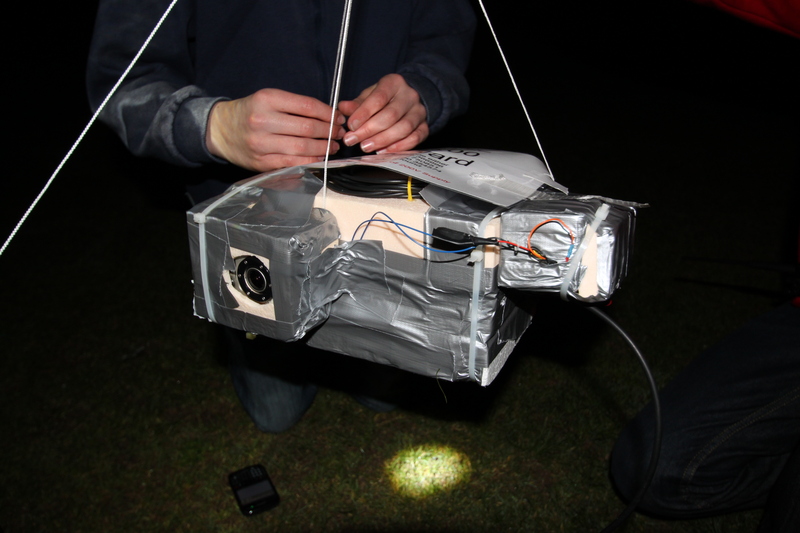

There were several things that were modified about the payload for this launch. Firstly, after the problems with frequency drift due to temperature and the consequential loss of decodeability, insulation was drastically improved this time around. In addition, the transmission regime was changed so that the payload transmitted a 300 baud packet twice, then another 300 baud packet twice, then a 50 baud packet. Each transmission was preceeded by a series of the "U" character, whose ASCII value contains alternating 0s and 1s to allow the receiver to settle.

The high voltage supply for the ionising radiation detectors was also better insulated in order to try and overcome the problems from launch one, where the detectors shut down at a certain altitude.

A GoPro HD video camera was also attached to the payload this time around, recording for the entire flight at 720p @ 60fps to a 32GB SD card.

A 5W white LED was placed inside the balloon neck to light up the envelope during launch. It flashed at regular intervals and was powered from a 9V PP3 battery.

Finally, we had problems during the first launch of the cameras cutting out. As such, a switch mode regulator was built to power the cameras from 6xAA Energiser Lithium batteries.

GoPro HD Camera in insulated box

Launch

We left Surrey at midnight (0000BST on Saturday 09/04/11) and headed straight up to Cambridge, where we picked up launch kit from CU Engineering Dept. We also picked up a Yaesu FT-817 and a 70cms whip for the second tracking car to use. From there, we headed to Churchill College and began preparing for the launch. A 1kW generator and a 500W site lamp were brought, and these were set up in the middle of the Churchill sports field. Some of the team were put to work assembling the payload, whilst others were charged with handling the payload, parachute and balloon rigging.

Payload assembly took longer than expected as the HD video camera and the HV box for the IRDs had not been integrated into the payload container, and this took some time. We began filling the KCI-1200 balloon at approximately 0435BST. We had to overfill the balloon a fair amount due to predictions showing that this would be required in order to keep the balloon away from the coast and the Thames estuary. We were aiming for approximately 5kg neck lift, which is relatively high.

Setting up the generator and lamp | Measuring neck lift of the envelope | Paying out the release cord

Filling and payload rigging was completed by 0510BST, and we commenced using a slow launch mechanism by which a release cord is fed through a loop on the balloon neck, and the balloon is fed gently into the air by paying out the release cord. The 5W flashing LED in the neck was not as visible as we had hoped, but still lit the envelope up very nicely. When the entire assembly is in the air, one end of the release cord is released, which pulls out through the loop on the balloon and the assembly lifts into the air. Unfortunately, during feeding out the release cord, it caught on a sharp cable tie edge on the payload, and broke. The entire assembly was dragged across the field for a few metres before lifting into the sky. Luckily, nothing was damaged, but the payload was swinging quite severely.

After verifying that telemetry was still being received and all onboard systems were still functioning correctly after the less-than-perfect launch, we packed up and headed off down the M11 to the predicted landing site around Hatfield Peveral. We overtook the payload fairly quickly, and by the time we reached our destination, the dynamic predictor was showing that the payload would fall short of us by several kilometers. As such, we headed North slightly, and arrived at the true landing site just 5 minutes after the payload.

During the drive down the motorway, we tested the uplink system. A PING command was sent to the payload when it was at roughly 15km altitude from a 5W 70cm handheld radio. The payload heard the uplink signal and replied in its next telemetry packet.

$$APEX,207,04:53:07,5205.7025,00018.5865,14275,070,120,08,

-14.81,-49.50,088,92B,00BC,00AC,59431F283,72,PING*C8FA

Recovery

The last packet heard from the air was at 0651BST at an altitude of 1282m, and we headed towards those coordinates. As we neared, we heard the RTTY transmissions, and pulled up a nearby hill into a layby to decode a transmission. We successfully decoded one of the 50 baud transmissions at 0705BST, and headed straight to those landing site coordinates. Finding the payload in the field was fairly trivial, and retrieval was simple. Most of the envelope was still attached to the nylon cord. It was noted that the downwards facing camera had turned off, whilst the horizontal one was still powered up and taking pictures.

Damage to the payload was mostly superficial, but the antenna was severely damaged and will require some repair before Apex II's next flight.

The payload as we found it in the field

Recovering the payload from the landing site

Post Flight Analysis

Looking at the images captured by the vertical camera, it is clear that the camera powered down on impact with the ground. It had taken images throughout the entire flight with no problems.

The flight computer has an onboard flash IC to which it is meant to write all the telemetry data so that a complete log can be downloaded after recovering the payload. Unfortunately on this flight, clearing the flash pre-flight did not work correctly, so no data from the flight was logged. This was not too much of an issue as most of the data was logged by tracking cars, the minibus, and other listening stations.

Due to the high swing and spin rate of the payload, a proportion of the photos taken were blurry. However, a good number were excellent -- we captured some incredible pictures of dawn over the Thames estuary and of the curvature of the Earth. The cameras had worked perfectly for the entire flight, so the switch mode regulator powering them had obviously worked flawlessly.

The HD video camera was enclosed in a waterproof case, which was difficult to open post-flight due to the vacuum that had formed inside it. The payload spinning made the video not as great as was had hoped, but a lot of the imagery is very good. The inside of the waterproof case had, however, fogged up due to condensation during parts of the flight. It seems from experience that leaving camera lenses exposed is the best method for overcoming this issue.

Payload disassembly after recovery

Tracks

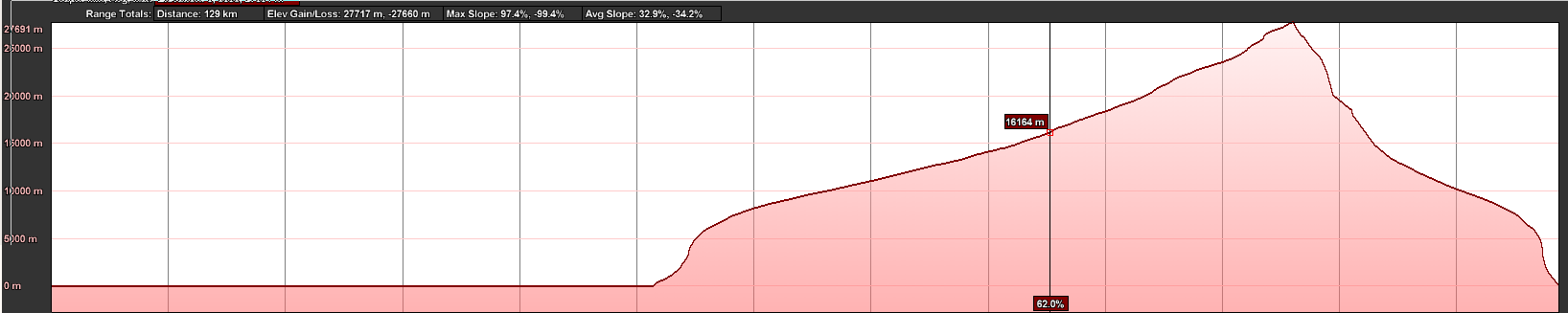

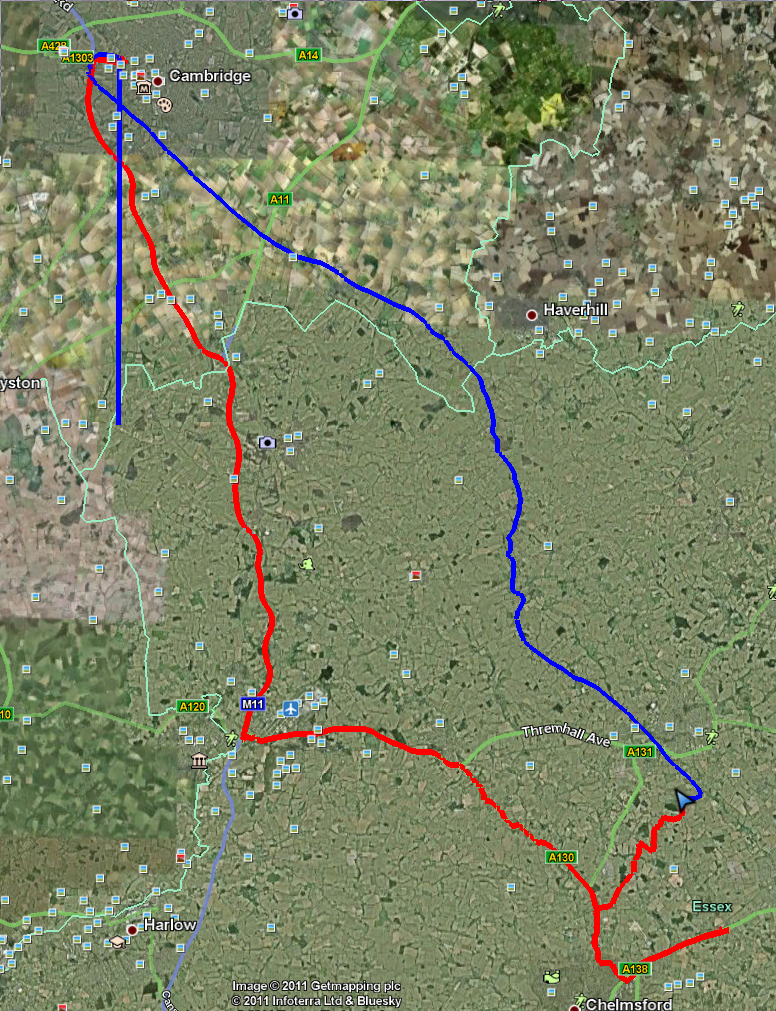

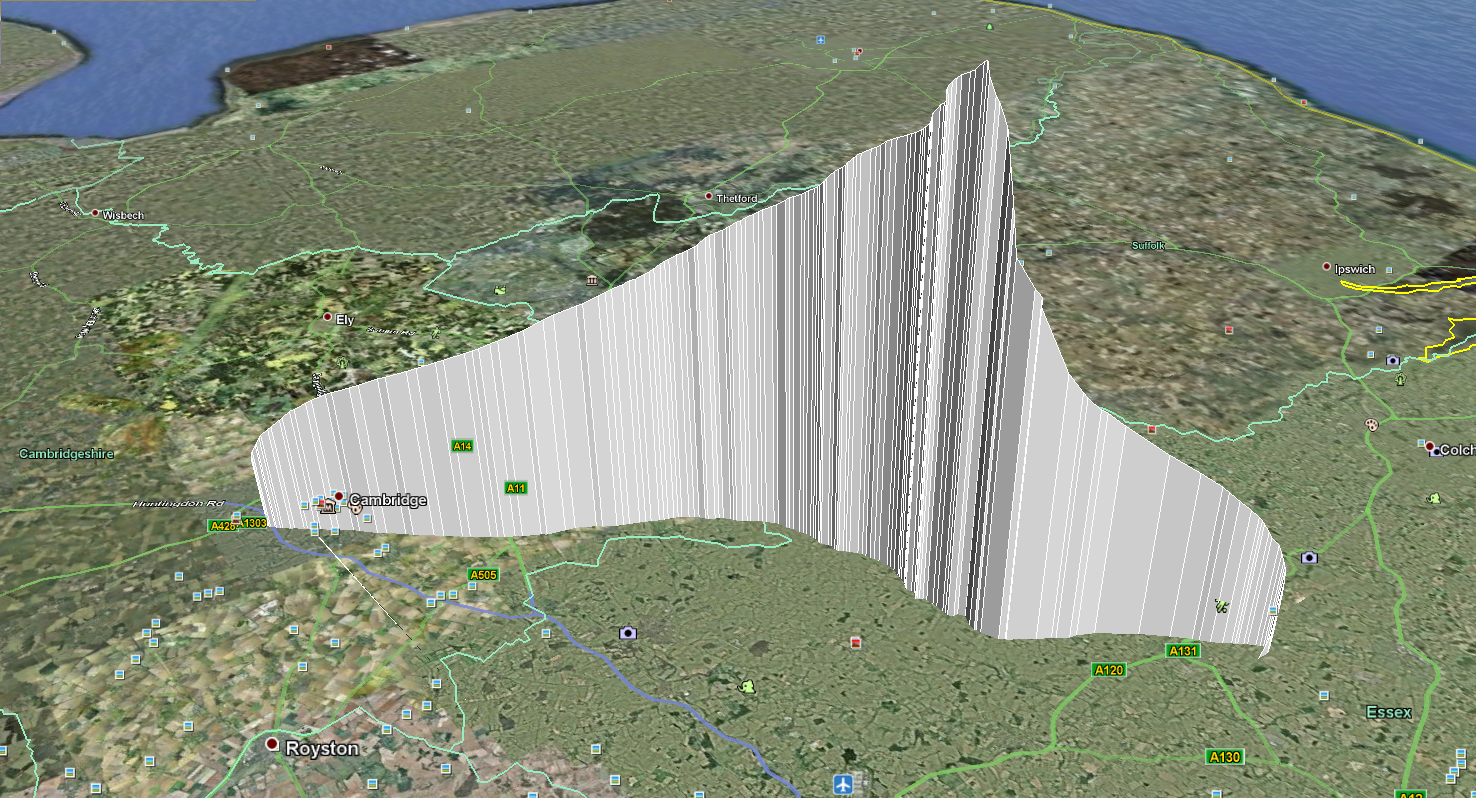

The tracks from the payload itself and from the chase vehicles can be seen below. Also shown is the elevation profile of the balloon during flight. The blue track is the balloon and the red track is the chase vehicles.

Flight Images

Here are a selection of the images from the onboard camera, showing dawn over the East coast of England and the Thames estuary. The complete set of photos can be found on the Project Apex image gallery.

Conclusions

At least one more launch of this payload is planned for the future. We aim to address the following issues before the next launch:

- Sort out the flash logging system on the flight computer so that we can download a full telemetry log post-flight

- dl-fldigi only uploads perfect packets, but error packets may be useful. A small logging program to connect to fldigi via a TCP socket and log all packets to a file would be useful.

- Sort out the HD video camera fogging

- More careful arrangement of the release cord and slow-release mechanism

- Payload as much assembled as possible before launch day

- Have chase car position plotted on the same map as balloon position

Team

The Apex II team

Members

- Jon Sowman (website/github)

- Matt Brejza (github)

- Ben Oxley (github)

- Andrew Cowan

- Dominic Branford

- Ed Branford

- Priyesh Patel

- Dan Saul

- Philip Warren

- Alex Landless

- Michael Woodgate